Global Health Care Waste-Treatment & Disposal: Challenges, Methods, and Future Directions

Healthcare waste (HCW) comprises all the waste types generated by healthcare establishments, research facilities, and laboratories. While only about 15% of HCW is classified as hazardous—containing infectious, toxic, or radioactive elements—the improper handling of all healthcare waste poses significant risks to public health, ecosystems, and the climate.

SOLID WASTE MANAGEMENT

Janani

8/4/20253 min read

Healthcare waste (HCW) comprises all the waste types generated by healthcare establishments, research facilities, and laboratories. While only about 15% of HCW is classified as hazardous—containing infectious, toxic, or radioactive elements—the improper handling of all healthcare waste poses significant risks to public health, ecosystems, and the climate.

What Is Health Care Waste?

Healthcare waste includes sharps (like needles and scalpels), pathological waste, pharmaceutical products, cytotoxic drugs, chemicals, and general waste similar to household refuse. The majority originates from hospitals, but significant amounts also come from clinics, long-term care facilities, veterinary services, and home healthcare.

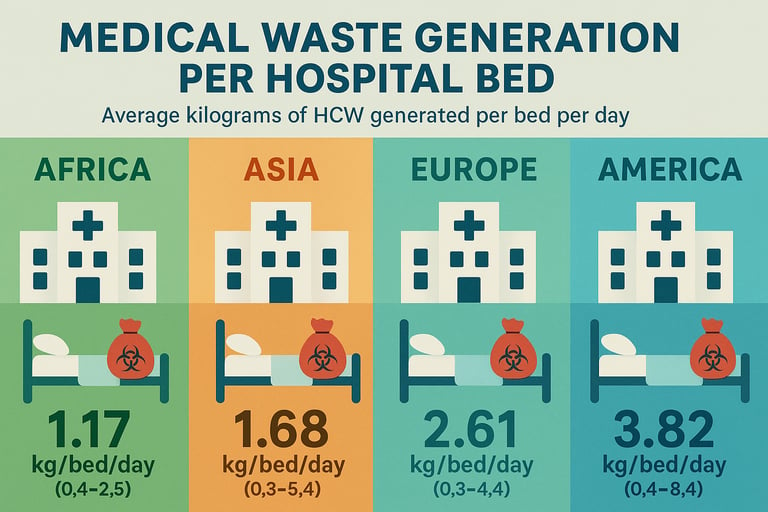

The global scale is staggering. In the United States alone—home to the world’s most waste-intensive healthcare system—over 3.5 million tons of HCW are generated annually. On average, American hospitals produce 15.3 kg per patient per day, resulting in around 6 million tons of waste per year, based on a population of 347 million. On a global scale, the healthcare waste disposal and management market was valued at $10.18 billion in 2025, projected to grow at a CAGR of 5.6% and reach $15.42 billion by 2033. Another broader estimate values the global medical waste management market at $39.8 billion in 2025, expected to nearly double by 2034.

These figures reflect not only the scale of waste generation but also the complex infrastructure and investment required to manage it safely.

Impact of Poorly Managed HCW

Poorly managed HCWs—especially in low- and middle-income countries (LMICs)—can cause direct harm. Infectious waste can spread diseases such as hepatitis, HIV, or bacterial infections, while toxic waste introduces heavy metals and hazardous chemicals into water and soil systems.

One particularly concerning practice is low-temperature incineration. When incinerators operate below the recommended threshold (typically <850°C), incomplete combustion can lead to the release of dioxins and furans—persistent organic pollutants (POPs) known for their carcinogenic and endocrine-disrupting effects. These substances bioaccumulate in the food chain and pose chronic health risks, particularly in communities living near improperly managed disposal sites.

Treatment and Disposal Practices

The handling of healthcare waste varies widely across regions depending on local infrastructure, regulatory enforcement, and economic resources. Key methods include:

1.Incineration

Still the most widely used method, particularly in high-income countries. High-temperature incineration (above 850–1100°C) ensures complete combustion and neutralization of pathogens. However, when operated at lower temperatures—common in under-regulated settings—it releases harmful emissions such as dioxins, furans, and heavy metals.

2.Autoclaving (Steam Sterilization)

Autoclaves use saturated steam under pressure to disinfect infectious waste. It’s an energy-efficient, scalable, and cleaner alternative to incineration for certain waste types, particularly sharps and soft waste.

3.Microwave Treatment

Microwave disinfection uses heat and moisture to inactivate pathogens. It’s suitable for urban facilities but requires consistent power and maintenance—challenges in many LMICs.

4.Chemical Disinfection

Common for liquid waste such as blood and urine. While effective, chemical disinfectants can themselves pose environmental risks if improperly handled.

5.Landfilling

Engineered landfills with leachate control and gas recovery systems are used for residual waste. However, in many regions, healthcare waste ends up in uncontrolled dumps, compounding public health and environmental hazards.

6.Encapsulation and Inertization

Used for pharmaceuticals and sharps, these techniques involve embedding waste in containers with cement or plastic matrices to prevent leaching.

WHO Recommendations

The World Health Organization (WHO) emphasizes a hierarchical approach to HCW management:

Minimization at the source through better procurement and usage practices.

Segregation of hazardous from non-hazardous waste using color-coded bins.

Safe handling with adequate personal protective equipment (PPE).

Environmentally sound treatment—with preference for non-burn technologies where feasible.

Proper final disposal, especially for residues like ash or chemically treated waste.

WHO also advocates for capacity building, policy enforcement, and investment in clean technologies—particularly in LMICs where open burning and uncontrolled dumping are still prevalent.

Toward Sustainable Solutions

As the healthcare waste market grows, it must align with the principles of sustainability and circularity. This includes:

Adoption of low-emission technologies

Digital tracking of waste streams

Public-private partnerships for infrastructure investment

Regulatory harmonization across borders

The tension between expanding healthcare access and minimizing environmental harm is a central challenge. But with rising global attention, regulatory pressure, and emerging technologies, there is a clear path forward toward safer, smarter, and more sustainable healthcare waste management.

Conclusion:

As global demand for healthcare services increases, so does the urgency of managing healthcare waste effectively. The risks posed by poor waste management—amplified by low-temperature incineration and hazardous emissions—are avoidable with the right investment and policy commitment. The industry is growing, but its success must be measured not only by market size, but by the health of people and the planet.